Recycling History

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Origins

Recycling has been a common practice for most of human history, with recorded advocates as far back as

Plato in 400 BC. During periods when resources were scarce, archaeological studies of ancient waste dumps show less household waste (such as ash, broken tools and pottery)—implying more waste was being recycled in the absence of new material.

[3]

In

pre-industrial times, there is evidence of scrap bronze and other metals being collected in Europe and melted down for perpetual reuse.

[4] In Britain dust and ash from wood and coal fires was collected by '

dustmen' and

downcycled as a base material used in brick making. The main driver for these types of recycling was the economic advantage of obtaining recycled feedstock instead of acquiring virgin material, as well as a lack of public waste removal in ever more densely populated areas.

[3] In 1813,

Benjamin Law developed the process of turning rags into '

shoddy' and '

mungo' wool in Batley, Yorkshire. This material combined recycled fibres with virgin

wool. The

West Yorkshire shoddy industry in towns such as Batley and Dewsbury, lasted from the early 19th century to at least 1914.

Industrialization spurred demand for affordable materials; aside from rags, ferrous

scrap metals were coveted as they were cheaper to acquire than was virgin ore. Railroads both purchased and sold scrap metal in the 19th century, and the growing steel and automobile industries purchased scrap in the early 20th century. Many secondary goods were collected, processed, and sold by peddlers who combed dumps, city streets, and went door to door looking for discarded machinery, pots, pans, and other sources of metal. By

World War I, thousands of such peddlers roamed the streets of American cities, taking advantage of market forces to recycle post-consumer materials back into industrial production.

[5]

Beverage bottles were recycled with a refundable deposit at some drink manufacturers in Great Britain and Ireland around 1800, notably

Schweppes.

[6] An official recycling system with refundable

deposits was established in Sweden for bottles in 1884 and aluminium beverage cans in 1982, by law, leading to a

recycling rate for beverage containers of 84–99 percent depending on type, and average use of a glass bottle is over 20 refills.

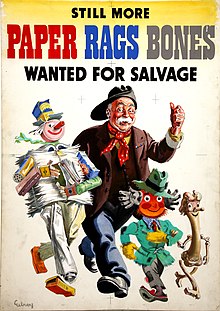

British poster from World War II

Wartime

Recycling was a highlight throughout World War II. During the war, financial constraints and significant material shortages due to war efforts made it necessary for countries to reuse goods and recycle materials.

[7] These resource shortages caused by the

world wars, and other such world-changing occurrences, greatly encouraged recycling.

[8] The struggles of war claimed much of the material resources available, leaving little for the civilian population.

[7] It became necessary for most homes to recycle their waste, as recycling offered an extra source of materials allowing people to make the most of what was available to them. Recycling household materials meant more resources for war efforts and a better chance of victory.

[7] Massive government promotion campaigns were carried out in the

home front during World War II in every country involved in the war, urging citizens to donate metals and conserve fibre, as a matter of patriotism.

Post-war

A considerable investment in recycling occurred in the 1970s, due to rising energy costs.

[9] Recycling aluminium uses only 5% of the energy required by virgin production; glass, paper and metals have less dramatic but very significant energy savings when recycled feedstock is used.

[10]

As of 2014, the

European Union has about 50% of world share of the waste and recycling industries, with over 60,000 companies employing 500,000 persons, with a turnover of €24 billion.

[11] Countries have to reach recycling rates of at least 50%, while the lead countries are around 65% and the EU average is 39% as of 2013.

[12]

For the lake in North West England, see Wast Water.

For the lake in North West England, see Wast Water.